Claudenicolas Ledoux Architecture Considered in Relation to Art Mores and Law

| Claude-Nicolas Ledoux | |

|---|---|

Ledoux by Martin Drolling, 1790 | |

| Born | (1736-03-21)21 March 1736 Dormans-sur-Marne, France |

| Died | Nov 18, 1806(1806-11-18) (aged 70) Paris, French republic |

| Occupation | Builder |

Project for the ideal city of Chaux: Business firm of supervisors of the source of the Loue. Published in 1804.

Claude-Nicolas Ledoux (21 March 1736 – 18 November 1806) was 1 of the primeval exponents of French Neoclassical architecture. He used his knowledge of architectural theory to design not but domestic architecture simply besides town planning; equally a consequence of his visionary plan for the Platonic City of Chaux, he became known as a utopian.[1] His greatest works were funded by the French monarchy and came to be perceived every bit symbols of the Ancien Régime rather than Utopia. The French Revolution hampered his career; much of his work was destroyed in the nineteenth century. In 1804, he published a collection of his designs under the title Fifty'Architecture considérée sous le rapport de fifty'art, des mœurs et de la législation (Architecture considered in relation to fine art, morals, and legislation).[2] In this volume he took the opportunity of revising his earlier designs, making them more rigorously neoclassical and up to date. This revision has distorted an accurate assessment of his part in the evolution of Neoclassical architecture.[iii] His nigh ambitious work was the uncompleted Regal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans, an idealistic and visionary town showing many examples of architecture parlante.[iv] Conversely his works and commissions also included the more mundane and everyday compages such as approximately lx elaborate tollgates around Paris in the Wall of the General Tax Subcontract.

Biography [edit]

Ledoux was born in 1736 in Dormans-sur-Marne, the son of a minor merchant from Champagne. At an early on age his mother, Francoise Domino, and godmother, Francoise Piloy, encouraged him to develop his cartoon skills. Later the Abbey of Sassenage funded his studies in Paris (1749–1753) at the Collège de Beauvais, where he followed a course in Classics. On leaving the Collège, historic period 17, he took employment as an engraver simply 4 years subsequently he began to written report architecture under the tutelage of Jacques-François Blondel, for whom he maintained a lifelong respect.

He and so trained under Pierre Contant d'Ivry, and also made the acquaintance of Jean-Michel Chevotet. These ii eminent Parisian architects designed in both the restrained French Rococo fashion, known as the "Louis XV style" and in the "Goût grec" (literally "Greek taste") phase of early Neoclassicism. Notwithstanding, under the tutelage of Contant d'Ivry and Chevotet, Ledoux was also introduced to Classical architecture, in particular the temples of Paestum, which, along with the works of Palladio, were to influence him greatly.

The two primary architects introduced Ledoux to their flush clientele. One of Ledoux's commencement patrons was the Businesswoman Crozat de Thiers, an immensely wealthy connoisseur who commissioned him to remodel part of his deluxe town house in the Place Vendôme. Another customer obtained through the auspices of his teachers was Président Hocquart de Montfermeil [five] and his sister, Mme de Montesquiou.

Early on piece of work (1762–1770) [edit]

Château de Mauperthuis, 1763 (demolished)

In 1762, the young Ledoux was commissioned to redecorate the Café Godeau, in the rue Saint-Honoré. The effect was an interior of trompe-fifty'œil and mirrors. Pilasters painted on the walls were interspersed with alternating Pier glasses and panels painted with trophies of helmets and weaponry, all executed in bold detail. In 1969 this interior was moved to the Musée Carnavalet.

The following year the Marquis de Montesquiou-Fézensac deputed Ledoux to redesign the old hilltop château on his estate at Mauperthuis. Ledoux rebuilt the château and created new gardens, replete with fountains supplied by an aqueduct. In add-on in the gardens and park he congenital an orangery, a pheasantry and vast dépendances of which little remains today.

In 1764, he designed for Président Hocquart, a Palladian house on the Chaussée d'Antin using the jumbo order. Ledoux would frequently utilise this motif that was condemned by the strict French tradition, which embraced the principle of superimposing the archetype column motifs on each floor, rise from simplest to the most complex: Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, etc.

Hôtel d'Hallwyll, Paris, 1766. Elevation of the facade on the rue Michel-le-Comte.

On 26 July 1764, in the Saint-Eustache Church, Paris, Ledoux married Marie Bureau, the daughter of a court musician. A friend from Champagne, Joseph Marin Masson de Courcelles, institute him a position equally the architect for the Water and Forestry Section. Here betwixt 1764 and 1770 he worked on the renovation and designs of churches, bridges, wells, fountains and schools.

Amid the even so extant works from this period are the bridge of Marac, the Prégibert span in Rolampont, the churches of Fouvent-le-Haut, Roche-et-Raucourt, Rolampont, the nave and portal of Cruzy-le-Châtel, and the quire of Saint-Etienne d'Auxerre.

In 1766 Ledoux began designing the Hôtel d'Hallwyll (Le Marais, Paris), a edifice that, according to the Dijon architect Jacques Cellerier, received widespread praise and attracted new patrons to the architect.[6] The owner Franz-Joseph d'Hallwyll (a Swiss colonel) and his wife, Marie-Thérèse Demidorge, were anxious to ensure work was executed economically. Therefore, Ledoux had to reuse portions of the existing buildings, the former Hôtel de Bouligneux. He had envisaged two colonnades in the Doric society leading to a nymphaeum decorated with urns at the human foot of the garden. However, the limitations of the site made this impossible, so Ledoux resorted to trompe-fifty'œil painting a colonnade on the blind wall of the neighboring convent, thus extending the perspective.

The recognition given to the relatively pocket-sized Hôtel d'Hallwyll led in 1767 to a more than prestigious committee, the Hôtel d'Uzès, on the rue Montmartre. There too, Ledoux preserved the structure of an earlier building. Today the panelling from the salon, an early case of the neoclassical way, largely carved by Joseph Métivier and Jean-Baptist Boiston to the designs of Ledoux, is preserved in the Carnavalet Museum, Paris.[7]

Pavilion of Mme du Barry, Louveciennes, 1770-1771

Ledoux designed the Château de Bénouville in Calvados (1768–1769) for the Marquis de Livry. With its uncomplicated, almost severe, facade of four stories, broken by a prostyle portico, the Château de Bénouville, while not one of Ledoux's most inventive plans, is notable for the unusual placement of the primary staircase at the center of the garden facade, a position normally taken by the main salon.[8]

Ledoux travelled to England in the years 1769-1771. There he became familiar with the Palladian style of architecture. Palladio, an influential Renaissance architect, was famous for his Italian villas (due east.1000., the Villa Rotunda). From this signal Ledoux worked often in the Palladian way, usually employing a cubic pattern broken by a prostyle portico which gave an air of importance even to a small structure. In this genre, he congenital, in 1770, a house for Marie Madeleine Guimard in the Chaussée d'Antin; and following that committee the business firm of Mlle Saint-Germain, in the Rue Saint-Lazare, the firm of Attilly in the suburb of Poissonnière, a firm for the poet Jean François de Saint-Lambert in Eaubonne, and most notably the Music Pavilion constructed between 1770 and 1771 at the Château de Louveciennes for the King'south mistress Madame du Barry, whose patronage and influence were to be of use to Ledoux in later years.[9]

Later works [edit]

His reputation established, Ledoux commenced a menses of however more than ambitious designs. The Hôtel de Montmorency on the Chaussée d'Antin dates from this period. It has a principal façade in the Ionic order above a rustic ground floor. Statues of illustrious members of the Montmorency family decorate the roof. Nonetheless, the depletion of the Montmorency fortune meant that Ledoux was required to execute the project with some parsimony.

In the yr 1775 Ledoux arrived in Kassel, Germany to become "Contrôlleur et ordonnateur des bâtimens de Hesse". Back in Paris, he received the plans for Museum Fridericianum and for the new entrance of the town, to correct them.[10] This work was finished in April 29th 1776. Of these corretions survived the plan for the first flooring of the Museum with the drawings and comments of Ledoux.[11]

Ledoux was interested in the work of the Regal Administrations Department and at times considered working for them, even though the positions they offered were often on the borderline betwixt architect and engineer. Through this interest in civic and municipal compages and due, in no small part, to the notorious influence of Madame du Barry, Ledoux was deputed with the modernization of the Salines de l'Est (Eastern Saltworks). The modernization was initiated post-obit the construction of the Burgundy Canal. In 1771 Ledoux was promoted to Inspector of the saltworks in Franche-Comté, a title he held until 1790, with the position yielding him an almanac bacon of 6000 livres.

The Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans (1775–1778) [edit]

Programme view of the facilities

In the 18th century salt was an essential and valuable commodity. The unpopular salt tax, known every bit the gabelle, was collected by the Ferme Générale. Salt served as a valuable source of income for the French king. In Franche-Comté, due to subterranean seams of halite, salt was extracted from saline wells past vaporizing in woods-fuelled furnaces.

In Salins-les-Bains or in Montmorot, the saltworks' boilers were congenital close to the wells, and the wood was brought from the adjacent forests. Contrary to what the French government wanted, Ledoux placed the saltworks near the woods as opposed to the source of the common salt water. He logically reasoned that it would exist easier to transport h2o than wood. Close to the first of these sites, the Fermiers Généraux decided to explore a more mechanized and efficient method of extraction, by constructing a purpose-built mill near the forest of Chaux, in the Val d'Flirtation. The saline h2o was to be brought to the manufacturing plant by a newly constructed canal.

The design, which received majestic approving, of the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans, or Salines de Chaux, is considered Ledoux's masterpiece. The initial building work was conceived every bit the first phase of a large and grandiose scheme for a new ideal metropolis. The commencement (and, every bit things were to turn out, merely) stage of edifice was constructed between 1775 and 1778. Entrance is through a massive Doric portico, inspired by the temples at Paestum.[12] The alliance of the columns is an archetypal motif of neoclassicism. Within, a cavernous hall gives the impression of entering an actual salt mine, decorated with concrete ornamentation representing the unproblematic forces of nature and the organizing genius of Human being, a reflection of the views of the relationship between culture and nature endorsed by such eighteenth-century philosophers as Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

The Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans: House of the director

The entrance building opens into a vast semicircular open air infinite that is surrounded by x buildings, which are bundled on the arc of a semicircle. On the arc is the cooper'due south forge, the forging mill and ii bothies for the workers. On the directly diameter are the workshops for the extraction of salt alternating with authoritative buildings. At the eye is the house of the director (illustrated), which originally besides contained a chapel.

The significance of this program is twofold: the circle, a perfect figure, evokes the harmony of the ideal metropolis and theoretically encloses a place of harmony for common work, but it recalls likewise gimmicky theories of organization and of official surveillance, particularly the Panopticon of Jeremy Bentham.

The saltworks entered a painful stage of industrial production and marginal profit, because of contest with the table salt-water marshes. After some not very profitable trials, it closed indefinitely in 1790 during the national instability caused past the French Revolution. Thus the dream of success for a manufacturing plant, conceived at the same fourth dimension as a regal residence and a new city, ended.

For a cursory period in the 1920s the salt works were reused but eventually closed due to contest. For the following decades, the common salt works lay in decay until they were named a UNESCO world heritage site and refurbished as a local cultural middle.

The theatre of Besançon [edit]

Théâtre de Besançon, 1784

In 1784 Ledoux was the architect selected to design a theatre at Besançon, Franche-Comté.[thirteen] The exterior of the building was designed as a astringent Palladian cube, adorned only by an almost Grecian neoclassical portico of six Ionic columns. However, if the neoclassical hints to the exterior was regarded equally modern then the interior was a revolution – venues for public entertainment were rare in the French provinces,[ citation needed ] and where they did be it was traditional that simply the nobles had seating, while those of less exulted rank had stood. Ledoux, realizing this was not only inconvenient simply elitist planned the theatre at Besançon on more egalitarian lines with seating for all just in some quarters such a plan was seen as radical if not revolutionary, the aristocracy had no wish to be seated alongside commoners. Notwithstanding Ledoux establish an ally in the Intendant of Franche-Comté, Charles André de la Coré, an enlightened man, he consented to follow this reforming plan. All the same, information technology was decided that the social classes would nevertheless be segregated thus while the theatre of was the first to have a ground floor amphitheatre furnished with seats for the ordinary paying public. Above them was a raised terrace or balustrade for land employers. Straight above was the starting time tier of boxes reserved for the aristocracy, and above this a tier of smaller boxes occupied past the middle-class the second. Thus Ledoux achieved his ambition that the theatre could at the same fourth dimension be a identify of social communion and shared entertainment while still maintaining a strict hierarchy of the classes.

The seating was non the only innovation at the theatre. With the aid of the machinist Sprint de Bosco [fourteen] Ledoux expanded the wings and back stage scenery apparatus, giving it greater depth than was customary, and many other modern improvements. Besançon was the outset theatre to screen the musicians in an orchestra pit.[ citation needed ] The building was widely acclaimed on its opening in 1784 just when Ledoux submitted plans for the proposed new theatre in Marseilles but they were not accepted.

In 1784, Ledoux was chosen over Pierre-Adrien Pâris for the construction of the new town hall in Neufchâtel. This was followed past the spectacular project that he conceived for the Palais de Justice and the prison of Aix-en-Provence. This projection, yet, was to be aggress by many difficulties. Trouble began in 1789 when construction was interrupted by the French Revolution, when only the ground floor walls had been completed [15]

Domestic and commercial compages [edit]

Ledoux was a Freemason[16] Ledoux took part, with his friend William Beckford, in diverse masonic ceremonies at the Loge Féminine de la Candeur which met in the town business firm he had congenital for Mme d'Espinchal, on the Rue des Petites-Écuries.

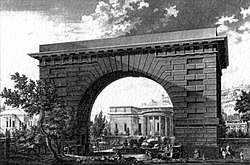

He was well acquitted with the earth of finance and those who inhabited it. He designed a large firm and park for Praudeau de Chemilly, the treasurer of the Maréchaussées, at Bourneville near Ferté-Milon. Ane of his more notable boondocks houses was for the widow of the Genevan banker Thélusson.[17] This classical mansion, a venue for Parisian high gild, was situated at the heart of a large landscaped garden accessed from the Rue de Provence. The house had an immense porte-cochere in the form of a pillared triumphal arch. The circular central salon, had at its center a colonnade which supported the ceiling.

On the Rue Saint-Georges, for the creole Hosten, Ledoux designed an ensemble of tenements for rental, designed in such a way they could in future be extended ad infinitum. In the Rue Saint-Lazare, effectually a commercial warehouse, he designed the gardens of Zephyr and Flora, which were illustrated by Hubert Robert.

Architecture for the ferme générale [edit]

Rotonde de Chartres (today: entrance to the Monceau park)

In the process of his work in Franche-Comté, Ledoux had become an architect for the ferme générale, for whom he built a salt storehouse in Compiègne and undertook to plan their vast headquarters on the rue du Bouloi in Paris.

Charles Alexandre de Calonne, the Controller-Full general of Finances, obtained on an idea from the chemist and fermier général Antoine Lavoisier, of drawing a barrier around Paris to limit contraband and evasion of the octrois, or internal community duties: this notorious Wall of the Farmers-General was to take six towers (one every 4 kilometers) and to incorporate sixty revenue enhancement-collecting offices. Ledoux was charged to design these buildings, which he baptized pompously "les Propylées de Paris"[xviii] and to which he wanted to give a grapheme of solemnity and magnificence while putting into practice his ideas on the necessary links betwixt form and function.

To cut curt the protests of the Parisian population, the operation was carried out apace: fifty barriers to access were congenital between 1785 and 1788. Well-nigh were destroyed in the nineteenth century and very few remain today,[19] of which those of La Villette and Place Denfert-Rochereau are the only ones that haven't been altered beyond recognition. In certain cases, the entry was framed with two identical buildings; in others, information technology consisted of a single building. The forms were archetypal: the rotunda (Heap, Reuilly); the rotunda surmounting a Greek cross (La Villette, Rapée); the cube with peristyle (Picpus); the Greek temple (Gentilly, Courcelles); the cavalcade (le Trône). At Place de fifty'Étoile, the buildings, flanked with columns alternating with cubic and cylindrical elements, evoked the House of the manager at Arc-and-Senans; at the Bureau des Bonshommes, an apse opened past a peristyle recalled the pavilion of Madame du Barry and the Hôtel de la Guimard. The order employed was by and large Doric Greek. Ledoux also used multiple rustic embossings.

This audacious structure met with political criticism,[twenty] as well as artful criticism of the architect, defendant by commentators such as Jacques-Antoine Dulaure and Quatremère de Quincy of taking excessive freedoms with the ancient canons. Bachaumont denounced a "monument d'esclavage et de despotisme" (a "monument to enslavement and despotism").[21] In his Tableau de Paris (1783), Louis-Sébastien Mercier stigmatised "les antres du fisc métamorphosés en palais à colonnes" ("the bastions of taxation metamorphosed into columned palaces"), and exclamed, "Ah! Monsieur Ledoux, vous êtes united nations terrible architecte!"(Ah! Monsieur Ledoux, yous are a terrible builder).[22] Ledoux, rendered the object of scandal by these opinions, was relieved of his official functions in 1787 while Jacques Necker, succeeding Calonne, disavowed the unabridged enterprise.

Difficult times [edit]

Portrait of Ledoux with his daughter. 1782 - Musée Carnavalet.

At the same fourth dimension, work on the law courts of Aix-en-Provence was suspended, and Ledoux was defendant of embroiling the Treasury in ill-considered expenditure. When the Revolution broke out, his rich clientele emigrated or perished under the guillotine. He saw his career and his projects stopped while at the same time the outset blows of the pickaxe began to ring on the already obsolete wall of the fermiers généraux. As of June 1790, the Ferme générale had been able to install its employees in the buildings by Ledoux, but the octroi (granting) was abolished in May 1791, which rendered the facilities useless. A symbol of fiscal oppression, Ledoux, who had amassed a handsome fortune, was arrested and thrown in La Force Prison.

He however made a project for a school of agriculture for the duc de Duras, his companion in captivity. Perhaps the intervention of the painter Jacques-Louis David, son-in-law of the entrepreneur Pécoul, and considerably enriched in the collection of the octrois, helped him avert the guillotine. Just he lost his favourite daughter whilst the other brought a lawsuit against him.

Ledoux, who was somewhen released, ceased building and attempted to set the publication of his complete œuvre. Since 1773, he had started to engrave his constructions and his projects but, considering of the development of his mode, he did non end retouching his drawings, and the engravers constantly had to redo their boards. Ledoux evolved towards an architecture e'er more detailed and colossal, with vast walls that were increasingly smoothen, and with increasingly rare openings. The differences between a drawing of the Pavillon de Louveciennes as information technology first was, made by the British architect Sir William Chambers and the engraving that was published in 1804 illustrate this process.

During his imprisonment, Ledoux had started to write a text to accompany the engravings. Only the start volume appeared during his lifetime, in 1804, under the title 50'Compages considérée sous le rapport de 50'art, des mœurs et de la législation(Architecture considered under the relation of fine art and legislation). It presented the theatre of Besançon, the saltworks of Arc-and-Senans and the town of Chaux.

He died in Paris in 1806.

Utopianism [edit]

Around the fourth dimension of the royal saltworks, Ledoux formalized his innovative blueprint ideas for an urbanism and an compages intended to improve society, of an ideal city charged with symbols and meanings. Forth with Étienne-Louis Boullée and his projection for the Cairn of Newton, he is considered a precursor to the utopians who would follow.[23] Boullée and Ledoux were a specific influence on subsequent Greek Revival architects and especially Benjamin Henry Latrobe who carried through the manner in the Usa for public architecture with the intention that the spirit of the ancient Athenian commonwealth would be echoed past buildings serving the new democracy of the United States of America.

After 1775 he presented Turgot with the commencement sketches of the town of Chaux, centered on the regal saltworks. The project, constantly perfected but never executed, was engraved beginning in 1780.[24] The engravings, announced in 1784 and probably all designed by 1799, were finally published in 1804, as part of the kickoff edition of his L'Compages considerée.[25]

Every bit a radical utopian of compages, didactics at the École des Beaux-Arts, he created a singular architectonic society, a new cavalcade formed of alternate cylindrical and cubic stones superimposed for their plastic effect. In this period, taste was returning to the antique, to the distinction and the exam, of the taste for the "rustic" way.

Works [edit]

Constructions [edit]

Hôtel de Mlle Guimard - Elevation

- Ornament of Café militaire (or Café Godeau), rue Saint-Honoré, Paris, 1762 (Musée Carnavalet, Paris)

- Château de Mauperthuis (Seine-et-Marne), 1763 (destroyed)

- Hôtel du président Hocquart, 66 rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin, Paris, 1764-1765 (destroyed)

- Hôtel d'Hallwyll, 28 rue Michel-le-Comte and 15 rue de Montmorency, Paris, 1766: It is the only private structure of Ledoux which remains in the capital.

- Hôtel d'Uzès, rue Montmartre, Paris, 1767 (détruit vers 1870): The boiseries du salon de compagnie take been conserved since 1968 at the Carnavalet Museum.

- Château de Bénouville, Bénouville, Calvados (about Caen), 1768-1769: Belongings of the general council of the Calvados, at the present it houses the chambre régionale des comptes.

- Hôtel de la présidente de Gourgues, 53 rue Saint-Dominique, Paris (reconstructed)

- Hôtel of Mlle Guimard, Chaussée-d'Antin, Paris (destroyed)

- Maison de Mlle Saint-Germain, rue Saint-Lazare, Paris, 1769-1770 (destroyed)

- Pavillon Saint-Lambert, Eaubonne (destroyed)

- Pavillon d'Attilly, faubourg Poissonnière, Paris, 1771 (destroyed)

- Pavillon de musique de Mme du Barry, Louveciennes, 1770–1771

- Hôtel de Montmorency, intersection of rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin and boulevard, Paris, 1772 (destroyed) : The woodwork of the circular salon are preserved at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

- Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans (1774–1779) (classified equally monuments historiques of France and a Earth Heritage Site of UNESCO in 1982)

- Théâtre de Besançon, 1778–1784

- Hôtel Thellusson, rue de Provence, Paris, 1778 (destroyed in 1826 at the fourth dimension the prolongation of rue Laffitte)

- Hôtel de Mme d'Espinchal, Rue des Petites-Écuries (Paris), Paris (destroyed)

- Parc de Bourneville, La Ferté-Milon (Aisne)

- Grenier à sel of Compiègne (Oise)

- Siège de la Ferme générale, rue du Bouloi, Paris

- Pavillons et barrières de 50'Octroi de Paris (see Wall of the Farmers-General) (1785).

Projects [edit]

Some of his other "visionary" designs:

- Project of the boondocks of Chaux, around the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans, published in 1804:

- Overall program

- Market

- Firm of the gardener

- Projection for the prison and police force courts of Aix-en-Provence, 1785–1786

- The project of immeuble-loyer , 1792

Publications [edit]

In 1804 was published a volume including the works from 1768 to 1789 : L'Architecture considérée sous le rapport de l'art, des mœurs et de la législation.

In popular culture [edit]

In Tite Kubo's manga serial Bleach, the character Zommari Leroux is named after Claude Nicolas Ledoux.

Notes [edit]

- ^ Vidler 2006, p. 10.

- ^ Digital re-create of Fifty'Architecture considérée at Gallica.

- ^ Eriksen 1974, p. 66.

- ^ Mallgrave 2005, p. 191.

- ^ Président Antoine-Louis Hyacinthe Hocquart de Montfermeil (1739-1794), president of the Courtroom of Aid of the Paris Parliament (1770), full general prosecutor (1778), President and starting time president (1789); subsequently he was executed during the Reign of Terror, his collection of paintings were declared nationals treasures and dispersed among provincial museums.

- ^ Braham 1980, p. 161.

- ^ Braham 1980, p. 167 (figure 215).

- ^ Braham 1980, p. 169.

- ^ Palmer 2011, p. 138.

- ^ Cornelius Steckner: Die "Verschönerung" von Kassel unter Friedrich Two. Andeutungen zur Stadtsanierung durch das Bau-Departement unter Johann Wilhelm von Gohr und Claude Nicolas LeDoux, in: Gunter Schweikhart (Hrsg.): Stadtplanung und Stadtentwicklung in Kassel im 18. Jahrhundert, Kassel 1983, p. 33-50.

- ^ Cornelius Steckner: Ledoux, Kassel und der Amerikanische Unabhängigkeitskrieg., in: XXVIIe Congrès International d'Histoire de 50'Fine art. 50'Art et les Révolutions, Strasbourg 1992, p. 345–372; Abb. 2-v.

- ^ Ledoux is not known to have travelled to Italy; Giambattista Piranesi had recently published engravings of the temples at Paestum, which effectively brought them into the European architectural repertory.

- ^ Camp, Pannill (4 December 2014). The First Frame. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN978-1-107-07916-eight.

- ^ a student of Giovanni Niccolò Servandoni

- ^ The current Palais de Justice was congenital nether the Bourbon Restoration by the builder Penchaud on the substructures of the building by Ledoux.

- ^ It is thought that he belonged to the Rosicrucian Order, either in Philalèthes or Éveillés.

- ^ a former associate of Jacques Necker

- ^ From the Greek propylaeum, a monumental gateway to a sacred enclosure

- ^ Identify Denfert-Rochereau, Identify de la Nation, Parc Monceau and at the edge of the basin of La Villette.

- ^ Pierre Beaumarchais, who saw it equally i of the causes of the Revolution, responded with his famous alexandrine "Le mur murant Paris, rend Paris murmurant" ("The wall walling Paris renders Paris grumbling.")

- ^ Mémoires secrets, October 1785.

- ^ Louis-Sébastien Mercier (1783). Tableau de Paris, nouvelle édition, vol. nine, p. 361.

- ^ Some examples of this continuation into the nineteenth and the start of the twentieth centuries: the Phalanstère of Charles Fourier, and the Familistère de Guise of Jean-Baptiste André Godin.

- ^ Gallet 1982, pp. 652–653.

- ^ Vidler 1996, p. 57.

Bibliography [edit]

- Braham, Allan (1980). The Compages of the French Enlightenment. Berkeley and Los Angeles: Academy of California Printing. ISBN 9780520067394.

- Eriksen, Svend (1974). Early Neo-Classicism in France, translated by Peter Thornton. London: Faber.

- Gallet, Michel (1980). Claude-Nicolas Ledoux (1736–1806). Paris.

- Gallet, Michel (1982). "Ledoux, Claude Nicolas", vol. 2, pp. 648–654, in Macmillan Encyclopedia of Architects, edited by Adolf Yard. Placzek. London: Collier Macmillan. ISBN 9780029250006.

- Gallet, Michel (1991). Architecture de Ledoux, inédits pour united nations tome 3. Paris.

- Gallet, Michel (1995). Les architectes parisiens du XVIII siècle : dictionnaire biographique et critique. Paris: Mengès. ISBN 9782856203705.

- Kaufmann, Emil (1952). Three Revolutionary Architects, Boullée, Ledoux and Lequeu. Philadelphia.

- Levallet-Haug, Geneviève (1934). Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, 1736-1806. Paris and Strasbourg.

- Lyonnet, Jean-Pierre (2013). Les Propylées de Paris, Claude-Nicolas Ledoux. Editions Honoré Clair ISBN 978-two-918371-16-eight.

- Mallgrave, Harry Francis (2005). Architectural Theory: An Album from Vitruvius to 1870 Blackwell Publishing. ISBN ane-4051-0257-8.

- Moreux, J.-Ch.; Raval, Marcel (1945). Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, architecte du Roi. Paris.

- Palmer, Allison Lee (2011). Historical Dictionary of Neoclassical Fine art and Architecture. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810874749.

- Rabreau, Daniel (2005). Claude Nicolas Ledoux, Monum, Paris. ISBN 2-85822-846-ix.

- Vidler, Anthony (1987). Ledoux. Paris: Editions Hazan. ISBN 9782850251252. Foreign Editions: Berlin, 1989; Tokyo, 1989; Madrid, 1994.

- Vidler, Anthony (1990). Claude-Nicolas Ledoux: Architecture and Social Reform at the Stop of the Ancien Régime. Cambridge (Mass.) and London: The MIT Printing. ISBN 9780262220323.

- Vidler, Anthony (1996). "Ledoux, Claude-Nicolas", vol. 19, pp. 55–58, in The Dictionary of Art, 34 volumes, edited by Jane Turner, reprinted with minor corrections in 1998. New York: Grove. ISBN 9781884446009. Besides at Oxford Fine art Online (subscription required).

- Vidler, Anthony (2006). Claude-Nicolas Ledoux: Architecture and Utopia in the Era of the French Revolution. Basel: Birkhäuser. ISBN three-7643-7485-3.

External links [edit]

- Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, 50'compages considérée sous le rapport de l'fine art, des moeurs et de la législation. Tome premier, 1804 (Gallica site: on-line publication)

- Site du bicentenaire de la mort de Claude Nicolas Ledoux - Saline d'Arc et Senans, 2006

- Claude Nicolas Ledoux on Empty Canon

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_Nicolas_Ledoux

0 Response to "Claudenicolas Ledoux Architecture Considered in Relation to Art Mores and Law"

Postar um comentário